The Domesday Book

The Domesday Book, also known Book of Winchester, was commissioned in December 1085 by William the Conqueror, who invaded England in 1066. The first draft was completed in August 1086 and contained records for 13,418 settlements in the English counties south of the rivers Ribble and Tees - the border with Scotland at the time. It covers 40 of the old counties of England, most of which still exist. The majority of landholders had accompanied William the Conqueror from France and were granted areas of land previously held by English natives.

England was divided into seven or more circuits. Each circuit was assigned three or four royal commissioners. Lists of manors and men for every county were compiled by the King’s tenants-in-chief, his sheriffs and by other local officials. When all the information had been collected, the commissioners visited special sittings of the county courts to test the accuracy of the information provided. Jurors were summoned from all the hundreds or wapentakes to verify the accuracy of the information under oath. The evidence would have been based on existing geld records and church payment lists. Some of the information provided would have been oral testimony.

The information was written down in Latin in ‘circuit summaries’. Much had to be edited out, but he remaining information was arranged into counties and then sorted by hierarchy of owner starting with the King. Under each owner the land was described by each hundred or wapentake and then by manor. The finished circuit summaries were the first stage in the writing-up process.

Domesday Book survives as two volumes. Little Domesday is actually far more detailed, down to numbers of livestock. It has been suggested that Little Domesday represents a first attempt, and that it was found impossible, or at least inconvenient, to complete the work on the same scale for Great Domesday.

The originals are currently housed in a specially made chest at The National Archives in Kew. Great Domesday is now rebound in two parts, and Little Domesday in three parts.

Below is the entry for Tutbury:

Translation:

“Henry de Ferrers has the Castle at Toteberie.

In the town about the castle are forty-two men who live only by merchandise"

Ferrers, Henry de

From Ferriers-St. Hilaire, Eure. Lord of Longueville, Normandy.

Castle at Tutbury, Staffs.

Domesday commissioner.

Ancestor of earls of Derby.

Large holdings in Derby and in 14 other counties.

Tutbury Toteberie: Henry de Ferrers. Market.

Norman church, once part of a Benedictine priory built by Henry de Ferrers.The castle dates back to the reign of William l.

Rolleston Rolvestune: Henry de Ferrers. Mill.

Head of a Saxon cross on the church tower. (The hall, once the home of Oswald Moseley's family, was pulled down in the 1920s.)

Background

During

the last years of his reign, King William had his power threatened from

several quarters. The greatest threats came from King Canute of Denmark

and King Olaf of Norway.

During

the last years of his reign, King William had his power threatened from

several quarters. The greatest threats came from King Canute of Denmark

and King Olaf of Norway.

In the Eleventh Century, part of the taxes raised went into a fund called the Danegeld, to buy off the marauding Danish armies.

One of the reasons for the book to be commissioned, was for William to see how much tax he was getting from the country.

The Domesday survey is a detailed statement of lands held by the king and by his tenants and of the resources that went with them. It records which manors belonged to which estates, thus ending years of confusion resulting from the dispossession of the Anglo-Saxons by their Norman conquerors.

It was a 'feudal' statement, giving the identities of the landholders who held their lands directly from the Crown, and of their tenants.

The fact that the scheme was executed in two years is a tribute of the political power and formidable will of William the Conqueror.

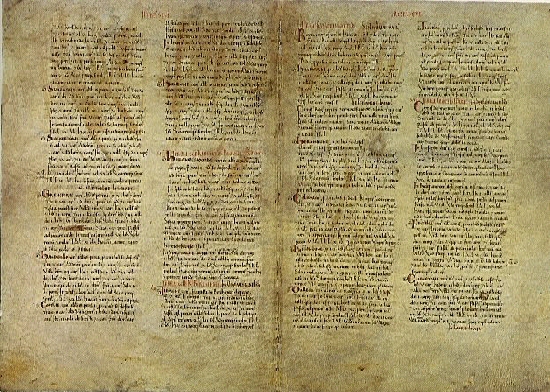

Part of the Domesday Book - the page size is actually 38cm x 28cm

One of the most important accounts of the making of the Domesday Book is that of an Anglo-Saxon chronicler who tells us that William -

..'had much though and very deep discussion about this country - how it was occupied or with what sorts of people. Then he sent his men all over England into every shire and had them find out how many hundred hides there were, or what land and cattle the king himself had, or what dues he ought to have in twelve months.

Also he had a record made of how much land his Archbishops had, and his Bishops and his Abbots and his Earls, and ... what or how much everybody had who was occupying land in England, in land or cattle, and how much money it was worth.'

...there was no single hide nor a yard of land, nor indeed one ox nor one cow nor one pig which was there left out: and all these records were brought to him afterwards."

Robert, Bishop of Hereford wrote this account -

The King's men ...'made a survey of all England; of the lands in each of the counties; of the possessions of each of the magnates, their lands, their habitations, their men, both bond and free, living in huts or with their own houses or land; of ploughs, horses and other animals; of the services and payments due from each and every estate.

After these investigators came others who were sent to unfamiliar counties to check the first description and to denounce and wrong-doers to the king. And the land was troubled with many calamities arising from the gathering of the royal taxes.'

In addition, documents dating from the Anglo-Saxon period which listed lands and taxes in existence, were drawn upon and each tenant-in-chief was required to send in a list of manors and men. In every town, village and hamlet, the commissioners asked the same questions to everyone with interest in land.

A contemporary publication at the time was the Ely Inquest, part of which reads -

...'They inquired what the manor was called; who held it at the time of King Edward, who holds it now, how many hides there are, how many ploughs in demesne (held by the lord) and how many belonging to the men, how many villagers; how many cottagers; how many slaves; how many freemen; how many sokemen, how much woodland; how much meadow, how much pasture, how many mills, how many fisheries; how much had been added to or taken away from the estate, what it used to be worth altogether, what it is worth now, and how much each freeman and sokeman had and has

All this was to be recorded thrice, namely as it was in the time of King Edward, as it was when King William gave it and as it is now. And it was also to be noted whether 'more could be taken than is now being taken.'

The information was written in Latin and this was then put into counties, landholders, hundreds or wapentakes, and manors.

The land was owned by:

King and family - 17%

Bishops and abbots - 26%

Tenants-in-chief - 54% - 190 of them

Some of the holdings were huge and a dozen or so barons controlled about a quarter of England. The great majority of Domesday landholders came from northern France, but there were still a few Anglo-Saxons and Danes.

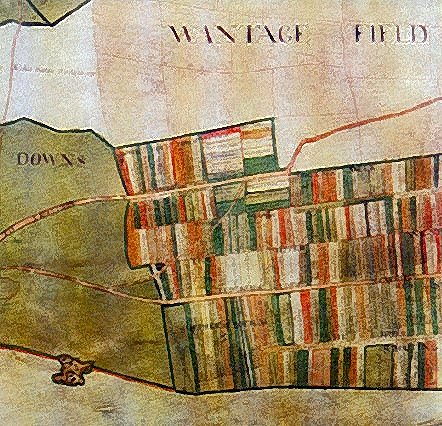

There were few castles and churches built in the 11th Century, most of the castles were built out of wood and consisted of a simple motte and bailey. Parish churches are not recorded systematically in Domesday but it gives details about them such as how they were divided into fractions between different owners. Habitations in most areas of the late 11th century followed a very ancient pattern of isolated farms, hamlets and tiny villages interspersed with fields. Over time these settlements gradually shifted or were abandoned.

The total value of the land in Domesday has been estimated at about £73,000 a year. The most common form of land ownership was under-tenancies, whose holders owed military services to their lords, and subsequently to the King. Another form was leasing or renting land for money, often large amounts. The value of an area of land and its resources was calculated according to size. In some areas, the values of the manors and their geld assessments are also connected, these are the figures in hides, virgates and carucates.

(Carucate, carucata, carrucata. Measurement of land in Danish counties, the equivalent of a hide.)

Domesday shows to some extent the cost of the Conquest on land values, which was particularly devastating in Northern England where many small villages were destroyed or damaged so badly their land values decreased by about a quarter since 1066. King William was partly to blame for his men's ruthlessness. Domesday records that the yields of the soke (the jurisdiction) of a hundred or wapentake went to the holder of the manor, while the earl kept a third of the money, the king reserved two thirds of that made from justice in the manor. The value of a manor was an estimate of the money its lord would receive annually from his peasants, including the annual dues paid by a mill or mine, a proportion of the fish caught or pigs kept, etc.

The population of England in 1086 has been estimated at between 1¼ and 2 million. Lincolnshire, East Anglia and East Kent were the most densely populated areas with more that 10 people per square mile, while northern England, Dartmoor and the Welsh Marches had fewer than three people per square mile, because many villages had been razed by the conquest armies.

In 1066 land was used like this:

Arable - 35%

Pasture / Meadow -25%

Woodland - 15%

Other - 25%

The arable land was used to grow wheat, barley, oats and beans. Domesday records over some 6000 water mills to cope with the heavy work of grinding the grain. Pasture was land where animals grazed all year. Meadow which was much more valuable, was land bordering streams and rivers, which was used both to produce hay and for grazing.

Sheep were of great economic importance and other animals include goats, cows, oxen and horses, wild horses and forest mares. Bees were also extremely important to produce honey and wax. Many of the references to fisheries are to weirs along the main rivers, but fishponds are also noted.