The Castle

The Castle has been the most important factor in the history of the town. In the iron age, about 2,500 years ago, Tutbury was a hill fort. When the inhabitants of the time found a suitable site, they would make their village on a hill - a few timbers and mud huts - and then protect it by a surrounding ditch and bank.

They would dig a ditch all round the village and use the earth that was dug out to make a protective bank on the inside. In this way they effectively got a wall twice the height.

They would put a wooden palisade on top of the bank and keep domestic animals in and wild animals out. Where they could, they would make two or three ditches and banks, one inside the other.

All this earthmoving was done without any mechanical diggers or indeed without any decent spades. It was done with the shoulder blades of oxen and such like. When you see the size of some of them you will appreciate that it was an enormous feat of engineering.

The best-preserved example in the country is at Maiden Castle in Dorset.

The Tutbury version was not as large or so well preserved, but you can still see it in places. It owes its majestic situation to the hill on which it stands.

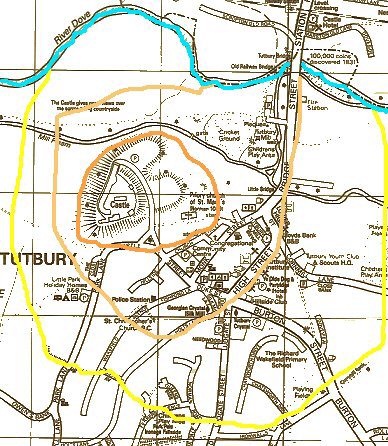

The outermost one started down at the river, came up to Burton Street, through the school grounds, down the back of Ironwalls Lane, across Ludgate Street, up the Park Pale, Ferrers Avenue, Wakefield Avenue, across Park Lane and turned round to meet up with the hill. The middle one has disappeared now. The innermost one was hard up against the Castle Hill and the bank that the Church Hall is built into, is all that remains of this one.

Estimated location of iron-age ditch and bank fortifications

They used the steep cliff on the northwest face of the hill and the River Dove on the northeast side. There was added protection on the NW as this was a marsh - the Tutbury Bog. In battles in later years, it was not unknown to lure the enemy around to attack from this side, so that they went splurge into the mud. It wouldn’t be easy to get out if you were a fully armoured knight on a fully armoured horse. Imagine what we would find if we dug down deep enough.

We can still see this outer wall:

- In the school grounds and across Chatsworth Drive

- Along the side of the Park Pale play area coming out into Ferrers Avenue by Hillcrest

- From the layby in Park Lane, turning round to come out from the top of Castle Street/Park Lane

It would have been higher and deeper and unfortunately a lot of it has been destroyed, even in recent years during house building work. It is now a protected Ancient Monument.

I’ll sidetrack for a moment and point out another ancient feature - one

of the oldest footpaths in the country along which farmers would wend their

way to the Corn Mill.

I’ll sidetrack for a moment and point out another ancient feature - one

of the oldest footpaths in the country along which farmers would wend their

way to the Corn Mill.

We’ll start near what became the old Sheepskin Shop - there has been a mill here for the last 1500 years, grinding corn using the power of the river.

From Cornmill Lane the path runs up to The Cliffe and comes out on the Burton Road near the bus stop.

In the 18th century there was a tollgate here. It continues along and down Ironwalls Lane to the junction with Ludgate Street and Belmot Road. There used to be a gate in the walls here known as Lud Gate. It runs up the side of the houses in Park Pale, and then disappears, reappearing where Wakefield Avenue joins Park Lane. From there it splits up to take the farmers home in various directions.

The

castle was built on an isolated rock with a deep fosse on three sides, over

90 feet wide and 40 feet deep and running into the cliff at each of its

extremities. This fosse was dug through the hill of red marl associated

with alabaster rock.

The

castle was built on an isolated rock with a deep fosse on three sides, over

90 feet wide and 40 feet deep and running into the cliff at each of its

extremities. This fosse was dug through the hill of red marl associated

with alabaster rock.

The

original entrance was between two large flattened mounds that would have

been defended by stockades of timber stakes, twined with thorn hedges and

where animals would be pastured.

The

original entrance was between two large flattened mounds that would have

been defended by stockades of timber stakes, twined with thorn hedges and

where animals would be pastured.

The fortifications were adapted and improved by the Anglo Saxons and soon after, Henry de Ferrers built the first castle that would have been a rough and ready wooden one.

Quite soon a stone one would replace it, and this was done by one of the early Ferrers Earls.

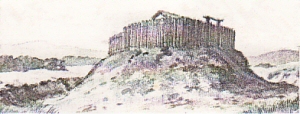

The original Norman Castle was of an early design known as ‘motte and bailey’.The motte is the mound, which is partly natural and partly man-made and the bailey is the courtyard.

They always built a tower, or keep on the motte for both defensive and residential purposes and you can see the remains of it in a 17th century print.

In this scene from the Bayeux Tapestry, castle building was forced labour.

In this scene from the Bayeux Tapestry, castle building was forced labour.

In 1174, however, William was rebelling against King Henry ll and the castle was destroyed but some of the bases of these walls remain.

The chapel in the middle of the courtyard was built about this time. The castle was re-built by 1201 when King John came to stay but in 1264 Prince Edward, who had escaped from Robert de Ferrers, demolished it again.

Edmund Crouchback (the first Earl of Lancaster) began restoration about 1270 and his son Thomas continued from 1298 onwards. He built a large hall, a range of buildings and what is mistakenly called John of Gaunt’s Gateway in 1313 - 14. This was made of sandstone and the 4,267 stones came from the quarry in Winshill. It cost £100.

He also built chambers and storage rooms that were still standing at the end of the 16th century, but remember the Battle of Burton Bridge - the castle was looted and damaged but not destroyed.

In 1326 when Thomas’s brother Henry took over, there were many facilities.

When John of Gaunt was the boss there are records of carpenters and masons building and repairing.

Between 1399 and 1406 a wall and tower were built using stone from Repton. In 1401 these walls were recorded as 20 ft high and 6 feet thick.

More new walls was built by King Henry lV between 1412 and 1418 and all through the 15th century new building and repair was undertaken using alabaster from Fauld and stone from Winshill.

The castle then starts to decay as it ceased to be the Lord’s principal residence. In 1516 the kitchen roof fell in and in 1523 a section of the wall split for 100 ft. It was still habitable when Mary was imprisoned (remember her comments about unsanitary conditions) but after that it continued to decay.

A survey in 1597 found repairs to the North Tower were needed but not carried out because the builder’s estimate of £200 was too much. In 1609 the delapidations were estimated at £1,000, but it was still habitable.

King

James l had the Main building replaced in 1631 to serve him on his hunting

trips.

King

James l had the Main building replaced in 1631 to serve him on his hunting

trips.

If you’ve been in the Banqueting Hall, you can imagine the King warming his bum in front of the big fireplace!

It was still defensible in the Civil War and withstood the siege of 1643, but surrendered at the second one in 1646.

It was finally demolished in 1647 on the orders of Oliver Cromwell who wanted to make sure that it wasn’t used against him.

Cromwell

instructed fifteen local men to do the work and paid them £2/10s/4d, but

they took two years over it and only did it half-heartedly.

Cromwell

instructed fifteen local men to do the work and paid them £2/10s/4d, but

they took two years over it and only did it half-heartedly.

Much of the stone and timber was taken away by the townspeople to use in the building of their own homes. We have several carved pieces in our own garden, including one with a coat of arms.

After the Restoration of the Monarchy, some rooms were repaired and in 1681 it was leased to Lord Vernon of Sudbury Hall, in whose family it remained until 1864.

It was one of the Vernons who built the ‘folly’ or mock ruin on top of the high mound. He thought that it improved the skyline and impressed visitors at Sudbury.

He also had the crinkly bits built on top of the house for some reason. Incidentally, there was a real tower on the mound originally. The folly has a big crack down the side now.

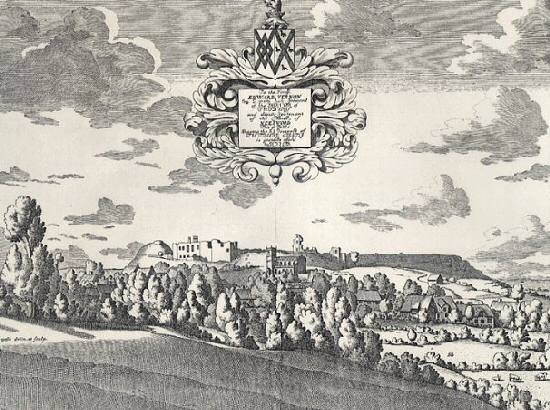

From the engraving of 1686, only a few years after it was knocked down by Cromwell's men, you can see that there is no folly (there are remains of a previous 'real' tower) and the 'crinkly bits' are not yet built.

The picture is dedicated to 'the Worshipful Edward Vernon - Deputy Steward of the Manor of Tutbury and Deputy Lieutenant of the Forest of Needwood'.

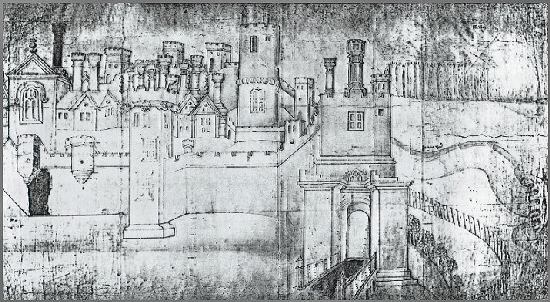

In this Extravagent picture of 1560, the artist has let his imagination run away with him, because some of the details are known not to have existed.

You can see quite clearly the tall North Tower, the great Gateway, the river and the bridge (which is in the wrong place and twisted round so that it would fit on to the page).

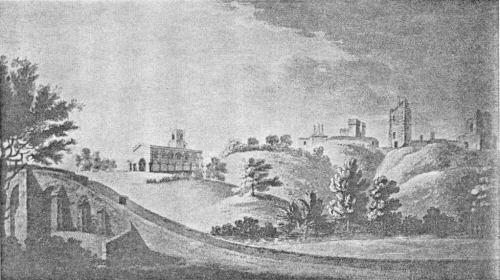

View of the Castle and Church from Tutbury Bridge in 1798

In the early 19th century the castle was converted into a farm and some buildings were added; in 1832, a proposal to turn it into a prison was rejected and by the mid 19th century the castle had started to become a tourist attraction. Admission charges were introduced in 1847 and it was also used for village fêtes but unfortunately these Victorians did a lot of damage and indulged in a lot of graffiti.

There was an extensive project of preservation undertaken in 1913 and in 1952, the farm ceased and the cow shed was turned into a tearoom!

In very recent years (1980 onwards) the castle has been used for fêtes, medieval banquets, reconstructed sieges, firework displays, wedding receptions, traction rallies and so on. Now in the 21st century the present custodian is sensitively restoring the castle and more of its history is gradually being revealed.

See the Tutbury Castle website >>

The reconstructed Garden

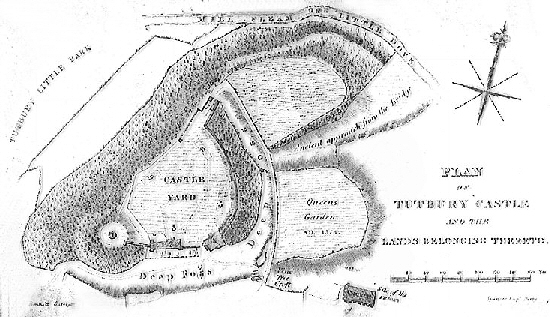

From the plan of the Castle drawn around 1840, you can see:

The ancient approach to the bridge and how the Castle is protected on the NE side by the river, and on the NW side by the cliff and bog.

View from the old railway over the River Dove

The Tutbury 'Bog'

Also on the other two sides by the moat - a 'deep foss' (partly natural) which has always been dry.

An ancient approach from the bridge protected by two outer baileys, one of which is marked the Queen's Garden after John of Gaunt's wife. One is now a field and the other is the car park. This entrance was abandoned about 1640 and the present approach substituted.

Inside the Castle yard, are the sites of some of the old buildings:

- The Folly.

- The current house on the site of the old kitchen.

- The site of the pantry and buttery.

- The South Tower with dungeons underneath.

- The site of Mary Queen of Scots Lodgings.

- The North Tower which formally contained 4 rooms.

- John of Gaunt's Gateway and the Porter's Lodge.

- The Steward's Offices.

- The supposed site of the 12th century St.Peter's Chapel, but now we

know that it is in the middle of the yard and was only excavated in the

1960s.

- A Norman well, which is 120 feet deep and lined with stone all the way down. Several coins have been found in it. It was repaired in 1437 because it was in danger of collapse. A reliable supply of water was of course most important, especially at times of siege.

The modern floor level is a couple of feet above the original level, as you will see if you look at the doorways and the chapel. This is because when the buildings (and they were throughout the courtyard) were pulled down and the walls and ceilings collapsed, all the unusable rubble was left lying there. Over the years it accumulated soil and grass grew.

A visitor in 1751 described how he had witnessed some demolition work and he saw 'great heaps of white plaster floor'. Underneath, much of it would have been cobbled and is probably still there. What goodies we might find if we could dig the rubble out!